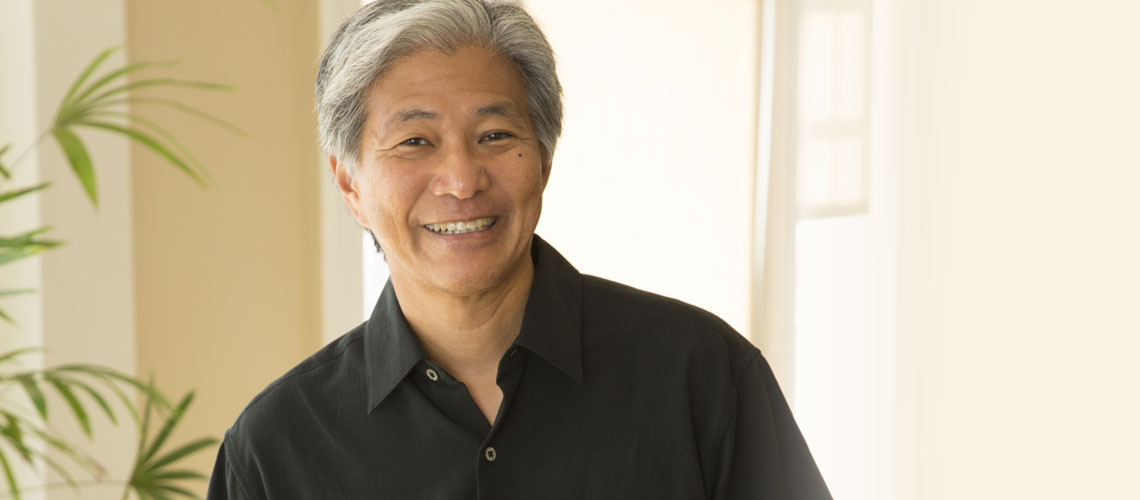

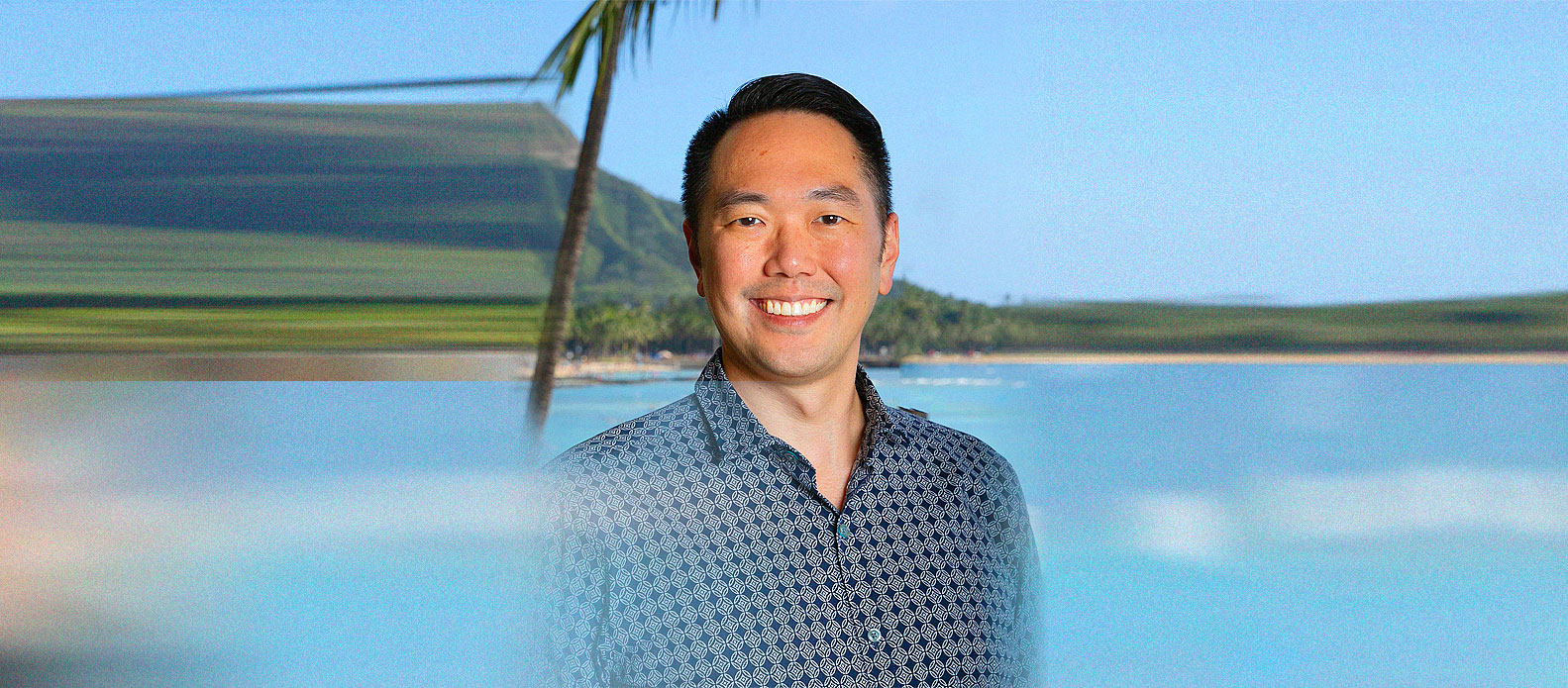

DAVID KA‘AHA‘AINA JR. is a licensed professional architect and the Hawai‘i regional business development manager at Allana Buick & Bers, a California-founded architectural engineering corporation with eight offices in the southeastern and western United States, focusing on building enclosure, construction management, mechanical and energy management and forensics services.

Kaahaaina is a Kamehameha Schools and University of Notre Dame graduate.

WHAT IS YOUR DESIGN PHILOSOPHY?

I believe strongly that there are designs suited to all climates and geographies, but that the best solutions are the vernacular— the ones that respond to specific climates or purposes. The Native Hawaiians understood their ‘aina, wai and kai, and managed the abundance of these resources.

Additionally, Western and Eastern cultures have now added to this understanding, and we have the opportunity to promote this blended style, or what I call “hapatechture.” It is taking advantage of building technology and systems, marrying them with sensitive and sustainable design concepts—keeping it simple yet elegant in that simplicity and letting our islands be the stars. And above all, function over form.

We owe it to na pua to make sure we create designs that perform. Our firm focuses on that design performance to make sure buildings are sustainable and durable.

WHAT’S YOUR ADVICE TO FUTURE ARCHITECTS, BUILDERS OR DESIGNERS?

Participate in the public discourse of planning, funding and constructing our built environment. Architects are keenly aware of the strength of design, the importance of durability and sustainability, and the impacts that these most public of art forms have on current and future generations. We must engage and lead the discussion so that all will benefit from our experiences.

WHERE DO YOU FIND INSPIRATION FOR YOUR DESIGNS PROJECTS AND THE CREATIVE ELEMENTS OF YOUR WORK?

I’m inspired by our forefathers, who wrought great works that are timeless—think ancient cultures, Classicism, the Renaissance. This can be brought forward, distilled and reduced down to the simple truths of managing and magnifying the elements through enclosure and siting.

Views, light, air, water and energy can be controlled and maximized to create great and productive places to live, work, learn, pray and play.

ARE THERE DESIGN CHALLENGES SPECIFIC TO HAWAI‘I?

There are far too many missed opportunities when it comes to the manifestation of modern Hawa‘i in our design. The 1950s and 1960s saw the post-territorial erection of Ossipoff structures and designs like the Arizona Memorial and the Board of Water Supply. In the 1970s, iconic structures like the Hawai‘i State Capitol and the Hyatt Regency Waikiki were built. The 1990s saw the construction of the Center for Hawaiian Studies, the Bishop Memorial Chapel, the Ihilani and the renovation of the Moana Surfrider. In the 2000s it was the NELHA Center and the Aulani. All of these had iconic placement and an interplay of climate, culture and materials.

The question now is how far new glass, steel and hardscaping technologies can take us to building the next iconic structure, one that is transcendent. The challenge is integrating form, time, culture and populism in a meaningful way. I look forward to that next great icon. I believe it is on a design board somewhere and just needs the chance to be manifested. Just look at the unbuilt designs for the Obama Presidential Library site in Kakaʻako or the design studio projects of students at the UH School of Architecture.

WAS THERE ANY ADVICE THAT GOT YOU TO WHERE YOU ARE TODAY?

My first college design studio professor said, “Work hard and play hard.” Architects are notorious for pulling all-nighters, for being obsessive and compulsive, and for having a very direct focus and train of thought. This is the work-hard element. We are taught to be meticulous, as an oversight can cost time and money, or it can be a matter of safety and health. However, the right brain also needs to be fed, hence the play-hard aspect—the embracing and expressing of the arts, of learning from travel or experience, from engaging in conversation, from working with ones hands. A famous football coach once said, “Show me someone who is a success and I will show you someone who has overcome adversity.” Anyone who has stood at the job site in front of a firing line of contractors, subs and owners’ reps and been asked “What do we do now?” knows what that statement means. Master both the right and the left brain, the work and play aspect, the adversity and opportunity equation, and you’ll be successful.

WHAT IS YOUR PERSPECTIVE ON THE CHANGING HONOLULU SKYLINE? DO MORE CRANES AND TOWERS EQUAL A HEALTHY BUILDING INDUSTRY?

In business development in the design profession, a healthy building industry is quixotic. If a firm thrives during new construction, then yes, cranes and towers mean a full project pipeline. However, if another firm focuses on repair and maintenance, on commissioning or post-occupancy work, on infrastructure, then perhaps not. The cycle is always build, maintain, repair, build. So the changing skyline is a reflection of that. It means growth and opportunity, but it also implies that the overall economy is vibrant and whole. There is a vast building industry that manages and maintains each building, hotel and home, and this is vital to our economy in more ways than people realize. As the cost to erect most buildings represents only 10 percent of the actual cost to operate and occupy it over its lifespan, resource management and maintenance are key to maximizing these investments. At ABBAE, we are committed to maintaining and creating durable, sustainable, functional buildings.

WHAT IS ONE QUESTION CONSUMERS SHOULD ALWAYS ASK THEIR DESIGN FIRM OR CONTRACTOR?

Why should I spend the money to ensure that the work is constructed the way it was designed? In other words, why do I need to monitor the trades in the field during construction? The answer is that a building is only as good as the builder, and the trades should never discourage that involvement, as it makes for a successful project overall.

The owner or consumer needs to realize that the project was a team effort, that skills and knowledge were applied to get the best value for their investment. Design doesn’t end when the permit is pulled, and building efforts begin long before that point as well. The truly successful projects are the ones that overlap and create synergy, when all teams assist one another in a holistic and pono way. Our firm deals with 70 percent of the issues related to building failure: leaks, energy overconsumption, structural defects or repairs. Taking the time during the construction process to look at these key issues goes a long way toward eliminating issues that affect building performance.

WHAT DOES IT TAKE TO SUCCEED IN HAWAI‘I IN YOUR LINE OF WORK?

Tenacity is the key to success in Hawai‘i. When I was a first grader, my father and I were fishing off the Nanakuli homestead where he grew up. My first-ever catch was a very small humuhumunukunukuapua’a. Thrilled, I went to take it off the hook. It bit me and hung on to my index finger for what seemed like minutes, until I flung it back into the water and it swam away.

To this day, that fish is a constant reminder that it’s not the size of the fish that matters; it’s tenacity. Sometimes you have to overcome gargantuan odds and simply hang on until an opportunity presents itself. Respect comes from working with others again and again, and success comes from that repeated commitment, engagement and overcoming of odds.